Gene and cell therapy is an exciting field of medicine that shows great promise to treat a variety of conditions, especially rare genetic disorders and certain forms of cancer. As is typical with medical advances, questions have arisen about the boundaries of ethical uses of these therapies. Two significant issues—germline gene editing and unapproved uses of cell therapies—draw questions about the responsible use of technology. By discussing and understanding ethical issues, patients and their families can engage in informed, shared decision-making with the medical and research community about how new technologies should be used.

What is Gene Editing?

Some types of gene therapy are designed to insert a working gene into a cell, while leaving the original, non-working gene present and unaltered. Gene editing is another type of gene therapy that removes, disrupts, alters, or corrects faulty elements of DNA within a gene of interest. Gene editing uses technology designed to make targeted changes inside the cell. In the US, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulates the process of developing, testing, and approving gene therapy products.

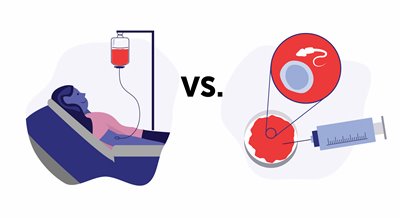

The gene and cell therapy approaches target somatic cells, the cells which make up the vast majority of tissues in the body except for sex cells (eggs and sperm). There is broad agreement among researchers, bioethicists, and other stakeholders that gene therapy, including gene editing, of somatic cells can be ethical approaches for the treatment of disease.

The gene and cell therapy approaches target somatic cells, the cells which make up the vast majority of tissues in the body except for sex cells (eggs and sperm). There is broad agreement among researchers, bioethicists, and other stakeholders that gene therapy, including gene editing, of somatic cells can be ethical approaches for the treatment of disease.

In order to understand germline gene editing, let’s define a few key terms and review the basics of human development. Our reproductive cells, known as germline cells or germ cells, are those sex cells (eggs and sperm) that pass on genes from parents to their children. Germline gene editing involves altering the specific genes of an egg, sperm cell, or early embryo (i.e., up to five days after fertilization) in a laboratory dish. Germline gene editing removes, disrupts, alters, or corrects faulty elements of DNA within a gene in sex cells.

Basic research of germline gene editing is ongoing, in which researchers perform studies of gene editing of these germline cells. In a basic research study, the edited germ cells are not implanted in a woman’s uterus with the goal of achieving pregnancy. The international scientific consensus is that it is premature to use germline gene editing clinically, or with the goal of achieving pregnancy.

Why Is There an Interest in Germline Gene Editing?

Clinical use of germline gene editing is prohibited in the United States, Europe, the United Kingdom, China, and many other countries around the world. Even so, it’s important to know why some might be interested in using the technique in the years ahead. Somatic gene therapies are often used to treat patients who have genetic diseases (learn more on our Gene Therapy Basics page). Somatic therapies involve transfer of genetic material to some targeted portion of our existing cells – and since one estimate says the average person has 37.2 trillion cells total, even a fraction of that is a lot of cells!

Parents who have or carry a faulty gene may be interested in germline editing technology. Early embryos only have a few cells, so the number of targeted cells for editing would be much smaller. As the embryo develops, those few edited cells would divide, and divide again, and could theoretically result in the birth of a child with many cells having the desired edit. An alternative to the embryo editing approach would be to edit the germ cells (egg or sperm) of one of the parents with the goal of then using in vitro fertilization (IVF) to create a fertilized embryo that has the desired genetic change (learn more about genetic inheritance on our Identifying a Genetic Disease page). However, it is important to emphasize that the clinical use of germline gene editing is prohibited in many countries at present for good reasons, owing to significant scientific, ethical, and safety concerns associated with its use.

Ethical Concerns for Germline Gene Editing

ASGCT’s position on germline gene editing practices is in line with the universal international consensus in the scientific community that it is neither safe nor effective at this time to use gene editing technologies on germline cells to attempt to prevent disease in a yet-unborn person, and that there are currently too many unknowns about this process for clinical use to proceed.

Let’s talk about specific safety concerns. Because genetic diseases are inherited, clinical use of germline gene editing would have potential multigenerational effects when the treated embryo develops, is born, and passes on the edited genes to children of their own. The potential benefits and potential harms for both the edited individual and the larger population may not be fully known or appreciated within the lifetime of the treated patient, and many generations would need to be studied to understand the long-term effects.

The potential benefit of clinical use of germline gene editing is that it might theoretically prevent a genetic disease in a yet-unborn person, but there are also substantial risks. Some risks are unknown, but others are well understood:

- As described earlier, the goal of gene editing is to make a targeted genetic change inside cells. Off-target effects are unwanted changes to the genome that occur in addition to the intended genetic change. All gene-editing techniques can create off-target mutations at locations in the genome other than the intended site. With clinical germline gene editing of very early embryos, off-target effects have the dangerous potential to exert their impacts on multiple organs and body systems. After all, the purpose of editing an embryo for clinical use would be to ensure the desired edit is included in all cells as the embryo grows; potentially dangerous off-target effects could be included in some or all cells, too.

- Mosaicism is a risk associated with clinical germline editing, in which multiple populations of cells that have different genetic makeups exist within a single edited person’s body. Mosaicism might occur if genetic editing happened after division of the initial single cell embryo into two cells. For example, if at the two-cell stage one of the cells acquires one type of edit while the other cell either has a different edit or no edit, mosaicism may result. Mosaicism is problematic because the genetic disease to be prevented may still occur if all the cells in the embryo do not have the desired edit. Perhaps more importantly, at present the effects of mosaicism are unpredictable; it could lead to entirely different kinds of disease or impact embryo development, potentially preventing development to term.

When considering the potential risks and benefits of clinical germline editing, it is worth noting that there is also an option for parents who are at risk for having children with a rare genetic disease, known as PGD with IVF. PGD, which stands for preimplantation genetic diagnosis, involves removing a cell from an embryo for genetic testing during the IVF process, before the embryo is transferred to the uterus. Only embryos that do not have the genetic disease are then implanted. Although there are also ethical considerations for this alternative method, its safety is more established than that of clinical germline gene editing. There are very few diseases that could not be treated by somatic gene therapy or PGD with IVF approaches.

The World Health Organization (WHO) is developing global standards for governance and oversight of germline gene editing. Simultaneously, an international commission convened by the U.S. National Academy of Medicine, the U.S. National Academy of Sciences, and the UK’s Royal Society is developing a framework to consider whether human germline genome editing could ever ethically be conducted and if so, under what circumstances. At present, there remains much controversy and concern over whether the clinical use of germline gene editing should be allowed in the future.