At any given time, there are thousands of active clinical trials—all testing treatments that someday may help slow, stop or even cure diseases. And even if there isn’t an existing trial for a specific disease, someday there could be. The development of a treatment has to start somewhere, and it doesn’t have to be an initiative from a large pharmaceutical company. It can often be grassroots support from a patient organization. There are a variety of required steps in the research and development of any new therapy, including a gene therapy, along with a variety of important resources that are needed as well.

Watch: Research Readiness for Rare Diseases

Check out this symposium from the 2024 Annual Meeting organized by ASGCT's Patient Outreach Committee on research readiness.

Preclinical and Clinical Trials

All new therapies being developed are tested in laboratory animals or cell-based models in preclinical studies before being considered safe enough to proceed into studies of patients. There are often many failures before a success is reached, meaning that early studies may prove ineffective or unsafe and therefore cannot move forward.

Research teams take every effort to use as few animals as possible during preclinical studies, and work hard to ensure that they are treated humanely. When possible, researchers use computer or cell-based models instead of animals. In preclinical studies, researchers investigate how a treatment is absorbed in the blood, how it is broken down chemically in the body, whether it can become toxic to the body, and other characteristics. These tests help show if the drug has any toxic side effects and establish approximate safe dose ranges for humans. If the results are positive, the treatment will transition from a preclinical study into a clinical trial with human patients.

Research teams take every effort to use as few animals as possible during preclinical studies, and work hard to ensure that they are treated humanely. When possible, researchers use computer or cell-based models instead of animals. In preclinical studies, researchers investigate how a treatment is absorbed in the blood, how it is broken down chemically in the body, whether it can become toxic to the body, and other characteristics. These tests help show if the drug has any toxic side effects and establish approximate safe dose ranges for humans. If the results are positive, the treatment will transition from a preclinical study into a clinical trial with human patients.

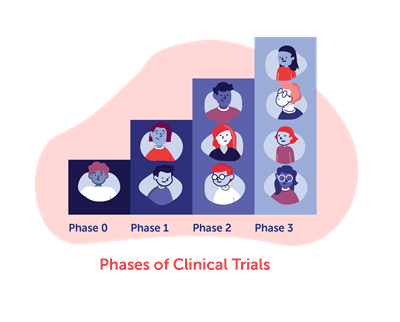

The clinical trials process is a learning process with timelines that can often change, sometimes taking eight years or more. This is because of different factors that go into each trial, including study planning, authorization to run a trial, funding, research materials, ethics reviews and more. Researchers need to first establish safe doses for patients and ensure that the data from the trial outcomes and follow up of patients is carefully analyzed. Other factors that will be looked at include number and frequency of doses, how long the effect is, if the treatment varies between patients, and any risks for specific patient groups.

Starting a Study

Clinical trials are typically sponsored and funded by pharmaceutical companies, academic institutions, federal agencies or patient organizations. Doctors and other healthcare providers can also sponsor clinical research. Each clinical study is led by a principal investigator, who is usually a medical doctor, and a research team of doctors, nurses and other healthcare professionals and researchers to support the safe and efficient running of the trial.

It can be challenging to find a clinician scientist who treats and studies a rare genetic disease and has the time and expertise to run a clinical study in small patient populations. Finding a research team, adequate funding, or even collecting enough initial data to properly plan a study can prove to be a daunting task. Clinical trials needed for FDA approvals of new drugs have a median cost of $19 million, and these studies come with lengthy time commitments for all professionals involved.

It can be challenging to find a clinician scientist who treats and studies a rare genetic disease and has the time and expertise to run a clinical study in small patient populations. Finding a research team, adequate funding, or even collecting enough initial data to properly plan a study can prove to be a daunting task. Clinical trials needed for FDA approvals of new drugs have a median cost of $19 million, and these studies come with lengthy time commitments for all professionals involved.

Here are some resources to check out:

-

Reference our list of U.S. Gene Therapy Centers if you are seeking gene therapy research for a rare disease.

-

The National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS) has a toolkit for Patient-Focused Therapy Development to provide information and resources to help patient groups support the process of developing a treatment or cure for their disease(s).

The Role of Patients and Advocates

Individual patients can take action on their own, but the reach, connections and collective power of a patient organization has an advantage in stimulating drug development. With this in mind, stimulating research can actually start with strengthening an existing patient organization (recruiting new members, fundraising, attending events) or even creating a new one if there is a need. The stronger a patient community becomes, the more effective they will be in helping a treatment through stages of drug development.

Data Collection is a way patients and advocates can help push clinical trials forward. The data may come in many different forms, but the goal is to gather or strengthen information about the disease for researchers to reference when planning a study. Relevant information may include: health data, demographics, lifestyle, family history, genetic data, clinical records, or physical samples.

Natural history studies are critical to informing a future clinical trial, drug development, and patient recruiting for these treatments. These are studies that collect information about how a disease progresses in the absence of treatment, which is often in the form of tissue donations from living or deceased patients. This is a way people with a disease can contribute to the research of that disease, even if a clinical trial isn’t available during their lifetime. This data is immensely valuable to researchers, as the information is typically unavailable or incomplete for most rare diseases.

Natural history studies are critical to informing a future clinical trial, drug development, and patient recruiting for these treatments. These are studies that collect information about how a disease progresses in the absence of treatment, which is often in the form of tissue donations from living or deceased patients. This is a way people with a disease can contribute to the research of that disease, even if a clinical trial isn’t available during their lifetime. This data is immensely valuable to researchers, as the information is typically unavailable or incomplete for most rare diseases.

Funding is also important to help get research started and keep momentum. Patient organizations can solicit corporate and federal donations, create fundraising campaigns, host events and apply for grants. The cost of getting a trial started varies, but can start at a few hundred thousand dollars. This is the cost of the required research to begin the trial process. Having a well-connected community helps with fundraising, advocacy for the disease and helping raise awareness in the general public. This visibility then can lead to support, additional fundraising, legislation and other actionable benefits.

Recruiting volunteers is another way to help once a clinical trial is active and recruiting (in need of participants). As the different phases of clinical trials progress, researchers need increasing amounts of eligible patients to participate. Finding the appropriate number of patients with a rare genetic disorder that fit the inclusion criteria for a safe study can be challenging for researchers. This can cause the research and development of a drug to stall even before it reaches the clinical trial phase. For studies being conducted in a limited number of locations, patient organizations may also be able to help pay for patient travel to study centers.

Setting realistic expectations is important, as is understanding that the road to develop a treatment is long, complicated, costly, and are ultimately experimental, so nothing is guaranteed. When research is unsuccessful, it doesn’t mean there is no hope for a particular treatment, but rather something unexpected may have happened or there wasn’t enough impact shown in a certain period of time. When research is successful, it can potentially change the lives of patients and their families forever.

A Mother’s Journey Stimulating Research

Written by Sharon King, Founder of Taylor’s Tale

We founded Taylor’s Tale in 2007 when my daughter was diagnosed with CLN1 disease, a form of Batten disease. Though a national organization already existed to support families and foster scientific progress, we felt starting our own public charity gave us—and children like Taylor—the best opportunity for a successful effort.

Taylor’s Tale began with an almost singular focus: to fund treatment development for CLN1 disease. We have helped advance important work in enzyme replacement therapy and small molecule therapy, but the most promising has been an innovative gene therapy research program for Batten disease that had its beginning at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Gene Therapy Center in 2013.

I met Dr. Steven Gray in late 2011 at a Batten disease workshop in Bethesda, Maryland. Dr. Gray presented his work in Giant Axonal Neuropathy (GAN) and the potential for a similar study in Batten. The GAN study could serve as a blueprint for the work ahead, possibly creating greater efficiencies in time and cost. I was excited for the opportunity to work with a talented and dedicated young investigator who shared my end goal—getting to the clinic.

“We’ll have to be relentless, you know. Nothing worth having is ever easy.”

Steven Gray, Ph.D.

Taylor’s Tale spent the next year learning more about gene therapy, following GAN’s progress and raising funds to support a CLN1 disease project in Dr. Gray’s lab. I reconnected with Dr. Gray at the International NCL Congress in London during the spring of 2012 and realized it was time to move a project forward. Taylor’s Tale spearheaded the alliance of several patient-driven organizations to fund parallel studies in CLN1 and CLN2 disease, and we announced our support of around $350-400K on Rare Disease Day 2013. The original grant was for a period of two years, and at the end of that time, the CLN1 data was very promising. Taylor’s Tale followed on with additional short-term funding until a new partner could be identified to complete the pre-clinical study.

In 2016, a clinical-stage biopharmaceutical company added Dr. Gray’s promising preclinical work to its pipeline. Since then, the company has been cleared to enter a Phase 1/2 clinical trial, following acceptance of an investigational new drug application in 2019.

Early on in our partnership, Dr. Gray told me, “We’ll have to be relentless, you know. Nothing worth having is ever easy.” It was good advice for any patient-driven organization helping to move forward a novel therapy.

More Resources

Check out this free course from the National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD) covering the complex world of drug development with a focus on rare diseases. Enroll in Rare Disease Drug Development: What Patients and Advocates Need to Know.